Scrum and Architecture

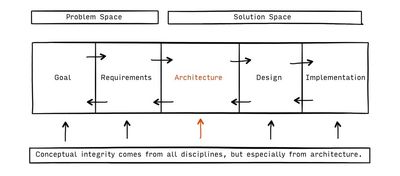

Scrum is team-oriented and separates the delivery process into subsequent iterations, so-called Sprints. The question arises how an architecture with conceptual integrity, an architecture that is intuitively understandable for users, developers and operators, an architecture that is easy to use even after many iterations, can be achieved while the team is focusing on the microcosm and the solution patterns of current iterations.

To achieve conceptual integrity, it has to be considered during the entire design and delivery process of a software solution. In this essay, you will find organizational and manual suggestions with the purpose to support conceptual integrity in the Scrum process. I will emphasize the role of the architect as an essential player with heavy responsibilities for the conceptual integrity of the software product.

Scrum and Architecture

The Agile Manifesto values „responding to change over following a plan.“ By taking this statement seriously, we accept that it makes sense to inspect our behavior and our achievements in a continuous manner. We do this to learn, to adapt and to come to better and more appropriate solutions while delivering results.

Scrum is a team-oriented management framework for agile product development that creates transparency and has this kind inspect and adapt built in. Work is being „done“ every two or so weeks, and at the end of these so-called Sprints, a process inspection and a product inspection is being held by the delivery team.

Software development is a learning process. After finishing a project, we usually know more than we did when we started the endeavor. This requires to make architectural decisions as late as possible to leverage the knowledge that has been obtained while delivering results because decision quality can be enhanced by following this approach. In addition to late decisions, we deliver working software as early as possible, to learn by doing, to avoid endless discussions and to use the momentum of done work. Ken Schwaber and Mike Beedle coined the statement „cut through the noise by taking action“ [Beedle and Schwaber 2002].

By putting these two behaviors together, we have an approach that can be called „deliver early and decide late“.

Deliver early and decide late

Architectural decisions are strategic for the solution space. They affect many aspects of the solution and will be recognized by the users of the product. Architectural decisions define the solution space for a given problem and bridge the gap between the requirements and the implementation. It is the architecture that allows adapting a software system with a reasonable effort for changing requirements.

Architectural decisions are being taken under two premises [Friedrichsen 2010]:

Represent and balance the interests of all stakeholders over the entire system lifecycle and minimize the total cost of ownership for the system during the whole lifecycle.

Here the balancing aspect of the interests of all stakeholders is emphasized. The famous Frederick Brooks [Brooks 1995:45] states, that

The architect of a system, like the architect of a building, is the user´s agent.

My impression is, both quotes are correct.

To me, design decisions, compared to architectural decisions, are of tactical or operational nature for the solution space. Design decisions make a structure inside of the solutions space, and the architectural choices span the solution space itself. The transition between architecture and design might be flowing.

The cooperative role model of Scrum does not explicitly mention the architects’ role. Except for the Product Owner, the Scrum Master and the Development Team no other roles are named. It is supposed that the members of the Scrum Team will self-organize and find suitable solutions.

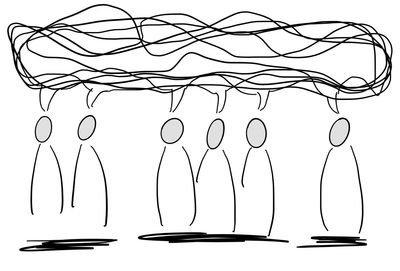

But in that model, how will architectural decisions be taken? Are they a result of a team-oriented brainstorming and is the decision „emergent“, as long as the decision is being taken „late“? How is it ensured that the decisions follow a consistent concept and lead to conceptual integrity? My thesis is that the cooperative derivation of architectural decisions improves decision quality, but that conceptual integrity can only be achieved for the system if the final decision-making competency is in the hand of one or at a maximum two closely collaborating individuals.

Human and process

Good architecture has conceptual integrity. One question is, can this be achieved by organizational measures, like processes and organizational structures, or is the expertise of an experienced and inspired architect of higher importance?

From the perspective of agile software development, the answer is easy to find. The first value statement of the Agile Manifesto states that „individuals and interactions are valued higher than processes and tools“ [Agile Manifesto]. Therefore in an agile environment, the architect always has a higher significance than any architecture process.

And there is even another reason to favor the person over the process. Software development requires social and communicating skills as well as engineering excellence and creativity. For an innovative product, creativity is a vital solution ingredient. Humans are creative, not so processes. , but any organization will only help if creative individuals in general and creative architects, in particular, are highly valued in the context of software development.

This does not mean that the organization can be overlooked when we design the fields of work. The organization is in service to make the communicative and social aspects of software development efficient. The structures we chose will be reflected by the product we create. „Conway´s Law“ [Conway 1968] gives us the essential point of view:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization´s communication structure.

Rephrased: Our communication structures will be found again in the product.

A complex organization with many employees and unclear responsibilities will lead to a bloated product. A lean organization with competent employees and clear responsibilities will produce a sharp and focused product.

Scrum with it´s underlying reduction-minded, team-oriented and result-oriented setup is an excellent tool to create sharp and focused products. The architect in Scrum is the helping hand to keep the conceptual integrity in the product.

Multi-team setup

In multi-team projects, it is likely that your teams are traditionally formed around architectural components. You may have a frontend and a backend team or a mobile and a web team with team leaders and the like.

This grouping of teams by components helps to bundle component know-how and to keep the components intact, but it usually does not contribute to delivering end-to-end features fast and without friction, because the teams are waiting for each other and blocking themselves. Communication is more difficult, takes more time and if the component teams are placed in different locations the hurdles are even higher.

With the only perspective of component teams, the project can quickly get into the fallacy of delivering only parts without end-to-end integration in each Sprint. A feature that can be inspected by a customer or a Product Owner will then only be visible after some Sprints.

Therefore I suggest the following approach: stay with the component teams – they help to bundle component know-how. But for the delivery of features also have virtual feature teams that consist of people from several component teams – merely those people who anyway need to come together to let the end-to-end feature become a reality. For these feature teams often a Daily Scrum makes much more sense than for a component team because they are hunting for a feature and use the Daily Scrum to ensure the end-to-end readiness and delivery of the function.

In such an organization component teams, virtual teams and the architect will discuss from time to time difficult changes (for example API changes) that belong to components. These changes may be required and indicated by a virtual feature team. And it may be the same person who suggests the need for a change from inside of the feature team, bringing it to his home component team, participating in the discussion and coming back with a solution approach to the feature team.

The virtual feature teams may change from time to time – whenever the next feature to be delivered requires a different team setup.

This multi-team organization, which forms a matrix with the axes feature and component will support both dimensions: the component architecture and fast, communication-oriented end-to-end feature delivery.

In the text below, when examining some tools for the architect, please refer to the End-to-End-Skeleton. This is a technique that supports feature delivery even in multi-team setups.

The architect in Scrum

Coming from the organization to the individual, we have to think about the architects’ role. Here are some suggestions to embed the architect into a Scrum endeavor:

- Embedded: If the architect is part of the Scrum Development Team or if a more separate position is needed, depends on the size of the project. If the entire project is made up of a single Scrum team, the architect will merely take his role inside of the Development Team. In case more than one Scrum Team is needed, the architect will have a more exposed position which is comparable to the exposure of the Product Owner.

- Decision competency: Analogous to the decision competency of the Product Owner regarding business decisions, the architect has the final word regarding architecture decisions. He helps to define the product.

- Member of the project: The architect is proactively responsible for the architecture of the solution space. And she is expected to have the same willingness to collaborate and drive to improve the development process as it is expected from all other team members.

- Coding skills: The Scrum Team accepts the architect. Her contributions enrich the product, and she provides benefits to the team. For software development projects it is inevitable that the architect can write code to understand technical details and working dynamics. In most cases, the background of an architect is technical. This requires her to be open and to be willing to learn the essential aspects of the business or problem domain.

This is a lot to expect from an architect. But the same is true for all other members of a Scrum Team. A developer is supposed to be on top of his craft, and a Product Owner must be able to influence his organization and have high competence in making business-relevant decisions to serve the product. The business experts need to be able to develop concise requirements and even test cases. Vice versa the architect must be able to fill out his role or at least has to learn the relevant aspects throughout the project.

Architecture by committee

Don´t do it. Companywide architecture committees that are being fed with decisions from under-ordinated projects and that guard, release or reject architectural decisions are a bottleneck for the enterprise and the involved projects. The parties are blocking themselves on the search for synergy. Responsibility is being carved out of the projects into the superordinated committee where focus, involvement, competence, and understanding are not bound to the projects that need the decisions.

Because of too many players with different interests the decisions being taken are often not focused enough and for none of the involved projects optimal.

Architecture by committee is the guarantee for a bloated product.

A companywide architecture committee should instead define constraints and architectural goals for the enterprise architecture and refrain from intervening the project work – except the project architect asks for it. To achieve results for real-world situations, it is helpful to have the same architects that work in delivery projects inside of the architecture committee. But it is essential to distinct committee goals and project work.

Project architects, on the other hand, have to follow the architecture constraints and goals given by the committee. Within this given space the architect derives architectural decisions on behalf of the project and in cooperation with the team. The architect is responsible for his choices – this includes the decision about how and when to involve the architecture committee.

Avoid architecture by committee [Brooks 2010:39]. The architecture is in the hand of the architect and not in the many hands of the committee. Architecture by committee is the guarantee for a bloated product.

Tools

In the following, I will propose some concrete tools that help the architect and the team to drive the architecture. These tools are mainly known in the IT architecture domain, and I will only make suggestions on how to use them inside of the Scrum process.

Start with the vision

The Product Vision contains and communicates the strategic goals of the endeavor. The vision will give self-organizational forces a direction. Whenever during the project course a decision needs to be taken, it must not contradict the goals of the vision.

One approach for developing such a vision is Geoffrey Moore´s elevator pitch. The basic idea behind is that you should be able to explain the greatness of your product idea during an elevator ride. You can use the following template to prepare the elevator pitch:

For [customer, user]

with [needs]

is [productname]

a [productcategory]

that has [attributes, values, a reason to buy].

Other than [competitor alternatives]

is [productname] a [differentiation of the product].

To go even one step further and anchor the vision within your business model, the Business Model Canvas by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur may be of use.

It is one of the Product Owners obligations to prepare a convincing Product Vision.

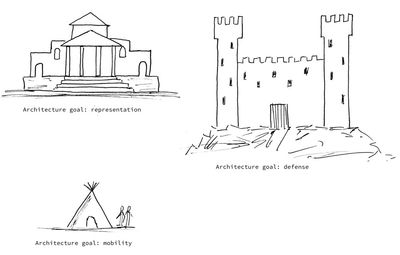

The architect has an interest in the Product Vision, too. Often architectural goals are bound to the product vision. These often non-functional goals may be explicit or implicit, but they are by definition of strategic nature. To identify and make them explicit is in the responsibility of the architect.

In addition to the business goals that are given by the Product Owner, the architect has to identify the relevant stakeholders and find the architectural goals by deriving them from the business goals. But keep in mind, the architect does not invent the architectural goals – she only makes them visible by deriving them from the business goals.

Architecture Vision

The architect will work closely together with the Product Owner to align the goals. Once identified, the architecture goals will be listed in an Architecture Vision statement or be embedded in the Product Vision.

As an architect you should not jump into a project if this work can not be done, otherwise, chances for project success are limited from the start. It is like the saying: „A shirt will never fit right if you miss the first buttonhole.“

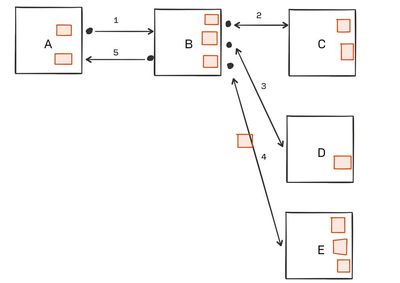

How important the knowledge of architectural goals are, can be seen in the following figures, that stand for different architectural goals:

Sometimes an Architecture Overview Diagram is part of the Architecture Vision. The Box-Bullet-Line notation can be of help to draw the diagram and visualize process flows between architecture components.

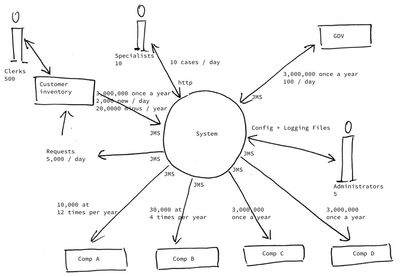

System Context Diagram

The System Context Diagram explains the environment of the system. The system itself will be seen as a black box. The important part is to understand the surrounding forces that affect the system with their input- and output-interfaces, system boundaries and responsibilities. Such forces are users as well as resources and other systems.

The system itself will be drawn as a circle in the middle of the diagram. All surrounding components, systems, and resources acting upon the system will be illustrated as boxes and users will be drawn as stick figures. Communication and data streams will be depicted as arrows between the system and the environmental forces.

Non-functional requirements, like the number of data records that have to be transmitted in a specific amount of time over a communication line or the number of users hitting the system at peak times, can be placed as weights beside the arrows or at the surrounding component boxes.

The System Context Diagram is of value in early project stages and throughout the entire project. It is best developed in a group effort together with the stakeholders of the system. By group-working, the different perspectives on the system can be visualized quickly, and the architect has a hook to communicate with the stakeholders. Just draw the system in the middle (use a Metaplan board or a whiteboard). The surrounding elements can be placed by using sticky notes or moderation cards. When leveraging this technique, you can quickly move the environmental factors around and develop your System Context.

Constraints

Technical or organizational limitations are to be considered in any project. Constraints limit the solution space that can be spanned by the architect. At the same time, constraints provide anchoring points for the solution architecture.

Constraints may be given by the presetting to use an enterprise-wide directory service, or by a time frame that is available for batch processing of data entries, or by queueing interfaces to existing systems. A given cost limit is a constraint, too.

To maintain the list of constraints that are of relevance for the project is a task for the architect.

Constraints are among the many factors that lead to non-functional requirements.

Non-functional requirements

Non-functional requirements often are system-wide and can therefore not be attached to a single User Story.

The strategic non-functional requirements lead to the architecture goals that will be documented in the Product Vision or the Architecture Vision.

But there are also non-functional requirements that will influence the system architecture and do not find their way into the vision statements. A good entry point to identify any non-functional requirements is the System Context Diagram. It helps to determine requirements regarding reliability, performance, scalability, security, and maintainability.

Because of the system-spanning nature of non-functional requirements, the architect must identify, document and communicate these requirements.

The list of relevant non-functional requirements has to be maintained by the architect. This list can be a part of the Architecture Vision or be a separate document.

Only in case, a non-functional requirement can be directly attached to a specific User Story, it should be documented besides the Story (e.g. in the acceptance criteria). In other cases, a separate document that collects all non-functional requirements serves the purpose better to understand the system stressors.

The architect has to transform the non-functional requirements into measurable quantities that allow the easy observance of compliance or violation. This gives all actors a direction and makes it easier to fulfill the requirement during development.

In particular, the following technique of the constraining resource needs this kind of measurable quantities.

Constraining resource

When crafting a system, the non-functional requirements, constraints and architecture goals will lead the project team to the limiting or restraining resources.

These resources give the fundamental limits that determine the performance of the system. The architect has to identify the scarce resources and derive allowable targets that can be used to measure and compare.

As an example:

2,500,000 data records need to be processed within one hour. Currently achieved value is 1,800,000.

The architet has to identify critical system limits, make them visible and establish an environment to measure continuously the current ability of the system to achieve the target.

The achievement of the target should be checked and communicated daily. This information will give direction for the delivery team and will foster self-organization towards the completion of the objective.

Box-Bullet-Line (BBL)

The Box-Bullet-Line diagram is a pragmatic way to visualize flows between components. It can be used to model the Architecture Overview (see above, Product Vision or Architecture Vision) or to model some details of the system.

The notation is intuitively understandable by the members of the project team. It fosters communication and is supporting a shared understanding of the systems structure and behavior.

Unlike the System Context diagram, which gives a black box perspective on the system, the BBL is a white box view. We want to understand what parts are essential and how the data and control flows between these parts.

Please refer to Box-Bullet-Line to get more details.

The BBL diagram can be used as a starting point for Storyboards and End-To-End-Skeletons.

Storyboard

In Scrum, we handle with requirements in the form of User Stories. The Product Backlog is an ordered list of User Stories.

A User Story does not explain how to build it. That is intentional. The User Story says what, why and gives context, but it does not tell the how to give room for self-organization.

The Storyboard supports the mapping from the „what“ to the „how.“ The relevant tasks for a specific Story will be visualized in the context of the components they belong to.

You start with a BBL diagram that contains the components you think are needed to build the Story. Draw the BBL on a flipchart or whiteboard. Now you break down the story into tasks by writing down each task on a sticky note and placing it on the component it belongs to in the BBL diagram.

This visualization helps all involved team members to identify the connection of the tasks. The mapping from User Story to tasks supports the goal of any architecture as an intermediary between business requirements and the concrete solution structure. The Storyboard improves the understanding of the solution structure for your User Stories.

End-To-End-Skeleton

In multi-team setups, an integrated feature delivery can be achieved by using the End-to-End-Skeleton technique [Brooks 1995:267]. By following this approach all components that are needed for a specific feature will be involved right from the start of development.

Essential is an initial interface definition between the components. Even this definition may change later, but you have to use a technical contract right from the start to model the end-to-end flow and make the programming efforts operational.

For sure it will occur that some functionalities will be developed later and some earlier. The later ones need to be represented by test doubles (like a stunt double in movies, but in software development, these doubles are mocks, fakes or stubs) [Fowler 2007]. The test doubles can produce some results for specific datasets but are no productive implementation of the needed functionality. Test doubles allow testing early some end-to-end flows.

The purpose of the End-to-End-Skeleton is a full-length flow through all components that are touched by the new feature. This ensures from the start an integrated view of all actors and the development is being bound to concrete interfaces. It becomes immediately visible if the full-length flow is interrupted at any point.

The technical specification of the interfaces should be in the hand of the architect or at least he should be part of the discussions that lead to interfaces, so that an over-arching understanding can be kept up and the data flow, as well as the interfaces, can be brought into the most straightforward possible format without duplicate or missing structures and attributes.

Architecture decisions

Architecture decisions represent the deliberate spanning of the solution space. Architecture decisions are anchoring points for further choices. Being such anchoring points makes architecture decisions challenging to change later on. With Stefan Zörner [Zörner, 2010] we can say

The one who is in charge of deriving architecture decisions in an understandable manner develops the architecture.

All aspects and tools that we have touched so far influence how architecture decisions are being taken.

Architecture decisions need to be communicated. Besides the spoken language, which is a central part, the written form cannot be omitted. By writing down architecture decisions, the entire team or project will be enabled to trace even long in the past taken decisions. Stefan Zörner [Zörner 2009] has a real practical approach for the derivation and documentation of architecture decisions, which goes merely by writing down the answers to the following questions:

- Problem

- What in detail is the problem?

- Why is it of relevance for the architecture?

- Which impacts does the decision have?

- Constraints

- What constraints need to be considered?

- What influencing factors need to be considered?

- Assumptions

- What assumptions have been made?

- What assumptions can be validated?

- What risks exist?

- Alternatives

- What alternatives have been examined?

- How is each of the other options being assessed?

- What alternatives are by intent being skipped?

- Decision

- What is the decision?

- Who took the decision?

- How is the decision being reasoned?

- When was the decision made?

I always find it helpful to go through these questions. It helps to clear the mind.

Conclusion

The here made suggestions are explicitly not meant to make the Scrum framework more complicated or to inject an additional hierarchical level just for the architect. Also, traditional architecture tools, of which only some are being mentioned here, should not be replaced by the here mentioned. Instead, these elaborations should describe what the architects’ role is about in the context of the Scrum role model and what concepts and tools are of use in that case.

The essay is a plea for the rights and obligations of the architect acting inside of the Scrum process; towards collaboration in the Scrum Team and against architecture by committee. I hope you can use some of the here made suggestions in your current or your next endeavor.

This text was first published in OBJEKTspektrum, issue 4/2011, under the title „Scrum und Architektur, konzeptionelle Integrität im Scrum Prozess“. I have reworked, enhanced and translated the initial document to publish it here on ulfschneider.io.

References

- [K. Beck et al.]

- Agile Manifesto, 2001, http://agilemanifesto.org

- [Beedle and Schwaber 2002]

- K. Schwaber, M. Beedle, „Agile Software Development with Scrum,“ Pearson Prentice Hall, 2002

- [Brooks 1995]

- F. P. Brooks, „The Mythical Man Month,“ Addison Wesley 1995

- [Brooks 2010]

- F. P. Brooks, „The Design of Design,“ Addison Wesley 2010

- [Conway 1968]

- M. E. Conway, „How Do Committees Invent?,“ 1968, http://www.melconway.com/Home/Conways_Law.html

- [Fowler 2007]

- M. Fowler, „Mocks Aren´t Stubs,“ 2007, http://www.martinfowler.com/articles/mocksArentStubs.html

- [Friedrichsen 2010]

- U. Friedrichsen, „Wer braucht einen Architekten? Über Ziele und Aufgaben von Architektur und Architekten,“ OBJEKTspektrum, Ausgabe 3, 2010

- [Osterwalder]

- Business Model Canvas, http://businessmodelgeneration.com/book?_ga=1.264929356.2127012834.1431598082

- [Schneider 2011]

- U. Schneider, „Scrum und Architektur, konzeptionelle Integrität im Scrum Prozess,“ OBJEKTspektrum, Ausgabe 4, 2011

- [Zörner 2009]

- S. Zörner, „Historisch gewachsen? – Entscheidungen festhalten,“ Java Magazin 04/2009

- [Zörner 2010]

- S. Zörner, „Gretchenfrage 2.0: Was unterscheidet Softwarearchitekten von Entwicklern?,“ Java Magazin 10/2010

Comments